My Written Exams Are Done!

Unfortunately the FAA doesn't just hand you a mechanic's certificate and tell you to have a good time drilling holes in airplanes. Actually, that's probably a good thing. Still, it means I have to jump through the appropriate hoops to get my little piece of plastic that allows me to sign off logbook entries stating the work I did to these aluminum tin cans called airplanes. On one hand it's scary working on something that carries people through the sky where people really shouldn't be, and won't be long if the airplane stops working. On the other hand, airplanes are just aluminum sheet metal structures crudely bent and riveted together (the factory workmanship isn't that good) with an oversized lawnmower engine on the front. The thing is you can't just replace parts on an airplane that easily. There are some modular things that you can swap out like tires, or instruments (if you're simply replacing what was there), or brakes, or vacuum pumps, or other things like that. But the thing I enjoy about aircraft maintenance is that it's still a trade built on craftsmanship. We make those crudely bent sheet metal structures by hand using a small variety of basic tools. And I enjoy that. I like to say that general aviation is one part Stone Age and one part NASA. Sometimes we're fretting over a .005" tolerance and sometimes we're beating sheet metal with a hammer and a block of wood. As the saying goes, "Hammer to shape, file to fit, paint to match." Experience helps you to determine which approach is necessary for a particular problem. Should I go ape on this or should I handle it like an unexploded ordinance? But, no matter how much experience you have, you can't legally do much without a little piece of paper telling people that, supposedly, you have the qualifications to know when you should use a hammer and when your should use a feather duster and a micrometer.

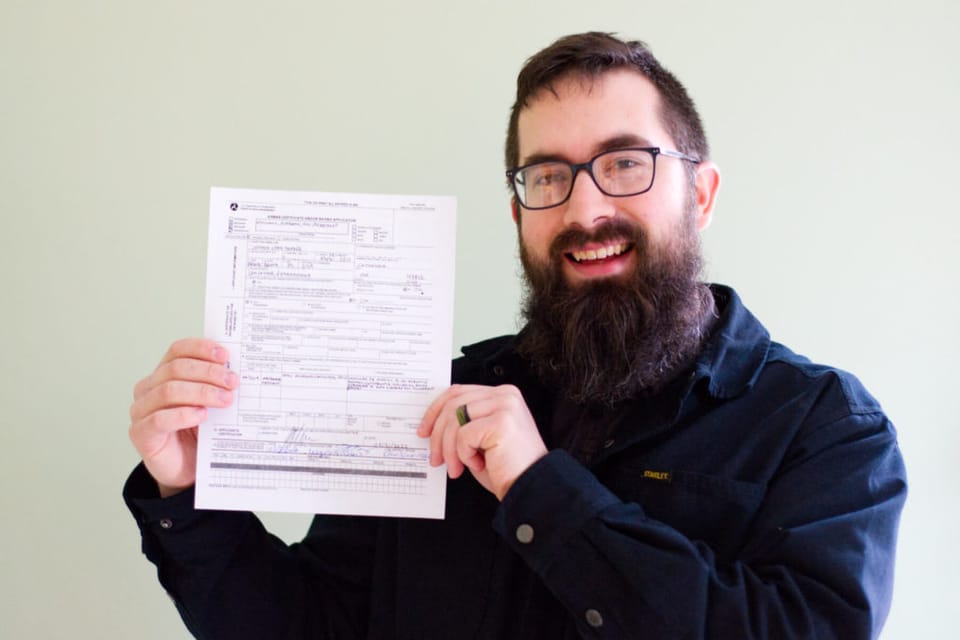

I completed the first few steps of this process this last week. On Thursday I went to the local FSDO (Field District Standards Office) here in Columbus to get my Authorization to Test (Form 8610-2 if you really wanted to know). Because I am not going through a curriculum based program at a school or university, I have to go apply for approval to test. I went in for my morning interview and had my brain gently prodded with aviation maintenance probes to see if the right answers came out of my mouth. It was a little intimidating but Steve, my interviewer, was an older gentleman with a kind voice and reassuring mannerisms. "You only have to get 50% of these questions right," he said. I liked those odds but still, being in the FAA building surrounded by people who've lived and breathed aviation for many more years than I was alive made me feel like a drooling neanderthal. We went over about 75 questions covering the general systems of an aircraft; Airframe, Powerplant, and General (math, physics, etc). "Do you have any experience doing X? Give me an example." As I was answering these questions it occurred to me that a lot of people who are in my shoes at that conference table have not had all the experiences I have had on such a variety of aircraft. MMS Aviation is a terrific program and the local FSDO respects it. I'm blessed to be in the position I am right now.

They signed my papers and sent me out the door. I had permission to take my exams! I have to say that my first personal experience with the FAA was a positive one and I suspect that's what Steve wanted. "We're here to help you do a good job," he kept saying. I believed him. Then again, I am pretty gullible.

The next day, Friday, I drove to Parr Airport in Zanesville to take my written exams. It was the closest PSI testing facility. When I hear the term "Testing Facility" I envision a university with armed guards making sure you don't cheat. This was nothing of the sort. It was a smattering of dilapidated hangars and several moss covered airplanes lurking around the shadows, tied to the ground like Gulliver on his travels. I wasn't sure which outbuilding to go to since they all looked less than official. Then I spotted a small sign that said, "Office." My sleuthing skills led me to a building which I found to be jammed full of airplane memorabilia: Model airplanes, old instruments, wrenches, a gurgling coffee maker surrounded by dairy free powdered creamer packs. There I met Valorie who was just the friendliest person ever. Apparently her and her husband Bob run the airport. Don't mistake my descriptions of the airport as disdain. I rather like it. It's a little slice of the best things about rural America, untainted by modern excess. Bob and Valorie aren't doing what they do because they get rich from it, they're doing it because they love it. I like that. Valorie led me outside to another outbuilding in which we found three computers and a small office, packed with even more airplane memorabilia. As we were entering my info in the computers, Valorie excused herself, leaned out of the door, and yelled at her husband to turn down the music in the adjoining hangar. I hadn't even heard it.

"I'm sorry for all the noise," She said.

I laughed. "I have kids," I said, "I'm used to it."

"Do you need earplugs to work?"

"I have kids," I said, "this is the least amount of noise I've heard in a few years. I'll be fine." Even if she sat on my shoulders and pulled on my hair, it still would've felt rather normal.

The worst part of taking the exams were hitting the "Exit" button. That's when the answers become permanent and your fate is sealed. I managed to get an 88% on my General, an 86% on my Powerplant, and an 88% on my Airframe. I was initially disappointed because I've never studied so much in my life and I was hoping for better. But I'm grateful, don't get me wrong. I guess if I can't be a perfect mechanic I'll settle for being a humble one.

Next week on Wednesday and Thursday I'll be taking my Oral and Practical tests at MMS Aviation. Chuck Egbert is on staff with MMS Aviation and is a DME. It'll be nice taking my tests with someone I know in a familiar setting. Pray that this humble apprenticeship could cross the threshold into being a humble mechanic.